At the turn of this century, Robert Putnam wrote the most depressing book for those of us who believe that there is no substitute for community. Putnam cited all sorts of indicators of the breakdown of social capital over the previous fifty years - closed pubs, fewer voters, less families eating together, and declining membership in Rotary, League of Women Voters, NAACP and other associations. The book was titled Bowling Alone because Putnam documented a dramatic loss in bowling leagues over the years.

I talked about Putnam's research in a presentation I made to the City Council of Port Phillip, Australia, and they encouraged me to visit the local St. Kilda Bowling Club. Sure enough, when I arrived at the large site next to Luna Park, I saw that the club had closed. In fact, there was a tombstone marking its demise. The inscription read: "Old bowlers never die. They just get composted." The former bowling club had been converted into a spectacular community garden!

Known as Veg Out, there are dozens of raised beds including one that looks like a pirate ship, another that resembles a ranch, and a garden planted in bathroom fixtures. There's a food forest, a cactus garden and abundant flowers. But there's also art everywhere. The old clubhouse is covered in murals and there's a large yellow submarine on its roof. Inside, artists are working with their neighbors to create more installations for the garden. Already, there are wrought iron gates, mosaic sculptures, a large sundial, a horse built out of garden tools, and a cow whose udders water the plants.

Veg Out is so much more than a garden. There's a cafe complete with a wood fired oven and a pub. For the children, there's a playground with a large sandbox. Children also enjoy the fairy garden with its gigantic toadstools and metal sculptures that move when cranked.

I visited on an especially active Saturday in spring. Children were playing hopscotch, getting their faces painted and visiting a petting zoo. People were eating fresh pizza and salads in the cafe. Dozens of families were seated on the lawn below a stage featuring local musicians. I'm sure that this was much more activity than the former bowling club had ever seen.

What I have come to realize is that people are finding new ways to build community. Robert Putnam was tracking the old ways. Yes, there may be fewer pubs than there were 50 years ago, but for every pub that has closed, there are many new coffee shops where people connect. Barn raising parties are less needed these days, but neighbors are coming together to build playgrounds. While there may be fewer bowling leagues, there are many more soccer leagues. Following are some of the new forms of community building.

Local Food Movement

Perhaps nowhere illustrates the power of food to build community better than the village of Todmorden, England. Through an initiative called Incredible Edibles, people from all walks of life are working together to raise vegetables everywhere - in the boulevards, the schools, and even the police station. Pamela Wharton who sparked the initiative says: "We are a very inclusive movement. Our motto is, 'If you eat, you're in."

There's another saying that "Flowers grow in flower gardens, but community grows in community gardens." Seattle has 95 organic community gardens with 10,000 people participating. Gardeners work together to build and maintain the gardens and to grow and deliver produce to local food banks. Instead of fences to keep people out, every garden has a gathering place to bring neighbors in. These are key bumping places where neighbors can connect on a regular basis and build relationships with one another.

Everywhere in the world I go, I see community gardens. In the small town of Corowa, Australia, retired men were recruited to build the gazebo, frog pond and rain catchment system for the community garden; in the process, they regained a sense of purpose and made good friends. Young people in a Nairobi slum have converted a dump into a garden. Havana has 1700 community gardens and even Singapore, where space is at a premium, boasts more than 1000.

In the Lower Hutt, New Zealand, community members converted an underutilized soccer field at Epuni Primary School into an urban farm. Neighbors worked together to build raised beds, a rain catchment system, a greenhouse from the panels of former slot machines, and even a library designed to look like a hobbit house complete with a green roof. This Common Unity project includes extensive vegetable plots, a food forest, beehives, and chickens. Neighbors assist students in preparing lunches from the farm's produce so that formerly malnourished children are eating fresh organic meals. A sign at the farm summarizes what community is all about: "We have two hands - one for giving and one for receiving."

Food forests, urban farms and community kitchens are now common throughout the world. On seven acres of land in the center of Seattle, neighbors are creating the Beacon Food Forest by planting and caring for fruit and nut trees and berry bushes that are available to everyone for picking. Seattle's Rainier Beach Urban Farm involves East Africans, local high school students, elders with dementia and many more in cultivating ten acres, harvesting 20,000 pounds of produce and preparing 6000 meals in the farm's community kitchen each year. One of my favorite community kitchens is the Free Cafe in Groningen, Netherlands which serves meals from salvaged food; young people built and operate the facility that includes an artistic kitchen, dining room, living room, library and composting toilets.

Seattle is famous for its historic Pike Place Market where the motto is: "Meet the Producer." Now, there are famers markets throughout the city where, in addition to meeting the growers, neighbors can meet and hang out with one another. Similar local markets can be found in cities and villages everywhere. Yes, there may be fewer families eating dinner together than there were 50 years ago, but the local food movement has created so many new opportunities to build social capital.

Environmental Restoration

Ever since the first Earth Day in 1970, communities have organized to safeguard the environment. The water protectors' courageous actions at Standing Rock are a recent example of the many attempts to hold corporations and government accountable. Increasingly, people are also coming together to undertake their own environmental restoration projects.

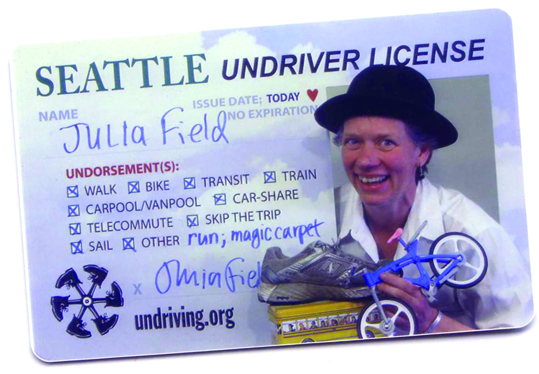

In 1994, Ballard was the Seattle neighborhood with the fewest number of street trees and the least park land outside of downtown. Dervilla Gowan responded by organizing her neighbors to plant 1080 street trees in one day. Other neighbors went on to build 20 park projects in as many years – pocket parks, playgrounds, community gardens, ballfields, green streets, a skate park, reforestation of natural areas and restoration of a salmon estuary. Their growing concern with climate change caused them to organize an annual Sustainable Ballardfest and issue undrivers licences which entitle the bearers to ride a foot-powered shufflebus. All of this has sparked a movement. There are now 67 neighborhoods and suburban towns that have joined Ballard to form SCALLOPS - Sustainable Communities All Over Puget Sound.

Taomi, a poor farming community in the mountains of central Taiwan, was at the epicenter of the 1999 earthquake. Amidst all of the devastation, the villagers took stock of their remaining assets and realized that they had abundant birds, butterflies and frogs. They worked together to build ponds and to reforest the land. Fifty famers got trained and certified as eco-tour guides. Young people created art with an environmental theme. For the first time, tourists began to visit. The locals started gardens, restaurants and bed and breakfasts. Now, Taomi is a beautiful eco-village that gets half a million visitors each year and boasts a much healthier economy.

The creeks flowing out of the Waitakere Ranges in west Auckland had become heavily polluted over time and the native bush on the banks had succumbed to all sorts of invasive vegetation. Through Project Twin Streams, neighbors organized to care for their respective sections of the creeks. Thousands of volunteers worked to remove tons of junk from the water. They weeded out the invasives and planted more than 800,000 trees and shrubs since the project began in 2003. Artists worked with children to create murals and sculptures all along the creeks to educate the public and to celebrate the clean water and the return of the native fish, bush and birds.

Such environmental projects usually aren't one-time affairs. Participants typically meet frequently to maintain and enjoy their contribution to the environment. In the process, they build community.

Community-Created Art

Many cities have long had commissions of experts who select individuals to create public art. There can certainly be value in this top-down approach, but taxpayers often question what the art means and how much it costs. A new approach to public art is on the ascendency. Just as planners, architects, police, public health workers and other professionals are learning how to use their knowledge and skills to empower communities, so are many artists. They are helping neighbors to use art as a way of expressing what is important to them – their history, culture, identity, values, environment or vision for the future. Through working together to conceive and create art, the participants also develop a stronger sense of community. The completed art often is a source of pride for the observers as well and helps them to identify with their community.

There are hundreds of examples of community-created art in Seattle thanks in large part to a Neighborhood Matching Fund that will be described later. One of the early projects was a gigantic troll that resulted from a community vote in the Fremont neighborhood and is now one of Seattle's most popular landmarks. Residents of Chinatown, Japantown, Manillatown and Little Saigon came together to design 17 dragons climbing utility poles defining a common International District. Gardeners at Bradner Park used mosaic tiles and broken dishes to create spectacular murals on the inside walls of their restroom as a successful strategy to combat vandalism. Neighborhood business districts were revitalized when the West Seattle community developed 15 historical murals for their storefronts and when Columbia City residents painted boarded up doors and windows to depict the businesses that they wanted to attract. Through Urban ArtWorks, artists have mentored over 5000 young people to create more than 1500 murals on walls previously covered with graffiti.

I see similar community creativity everywhere. When I visited an art center in Auckland's former Corban Estate Winery, young offenders were passionately painting a mural they had designed for a police station and there was a building where homeless Maori were proudly creating art and crafts. In Gosford, Australia, residents handcrafted 40,000 poppies that were installed around Memorial Fountain to commemorate the centenary of the Anzac landing at Gallipoli. Maple Ridge, British Columbia has an Artists in Residency program through which the city makes houses available to artists who work with their neighbors to create installations or stage events such as the River Festival I enjoyed complete with salmon lanterns lighting the way. Nothing good was happening in Tacoma's Frink Park until someone saw the potential of that concrete-covered space as a canvas; now there is free chalk available every Friday and dozens of people from all walks of life can be seen creating art that visitors enjoy until the next rain.

Placemaking

Most of our neighborhoods were designed by outside professionals – planners, architects and developers. Increasingly, though, residents are working together to create a unique identity for their neighborhood and to shape places where they can bump into one another on a regular basis. Community-created art typically plays a large role in this process of placemaking.

There's a good example of placemaking in the Newton neighborhood of Surrey, British Columbia. In the center of the business district is a lot covered by very tall trees. Many neighbors complained about the drug dealing, encampments and other public safety concerns hidden in the trees. The police suggested that the sight lines could be improved by clearcutting this mini-forest, but other neighbors had a better idea. They decided to turn the problem space into a community place, and they gave it a name - The Grove. Creative ways were found to use the trees: frames were installed on each tree so that neighbors could display their art; a tightrope was extended between two of the trees; a large stump was painted to serve as a chessboard; word cards were placed on a trunk so that they could be rearranged on what is known as the Poet Tree (three volumes of poetry have now emerged from The Grove). Strings of lights were hung to brighten the environment at night. Neighbors built Encyclopedia House from outdated editions discarded by the library. Local musicians were invited to perform in The Grove. Every major holiday and some minor ones like Groundhog Day are celebrated there. Workshops on everything from poetry writing to seed bombing are accommodated. Welcome signs in every language of that very diverse neighborhood invite people in. And it works! Not only do people feel safe, but The Grove has helped very different people, some of whom had been seen as a problem, to meet one another and build a sense of community.

With the budget cuts in Rotterdam, a neighborhood association was gearing up to fight the closure of their public library. But someone argued that the library wasn't all that great and that the association's energy could be better used to create their own place. Community members got excited about this vision and developed the Reading Room in a vacant storefront. It includes a library, cafe, pub, children's play area, boxing rink and stage for regular performances. It attracts many more people than the former library and gets them to interact with one another - something that most libraries aren't programmed to do. Everything in the space was donated and the staff are all volunteers.

Placemaking ideas are spreading rapidly. The Sellwood Neighborhood in Portland, Oregon painted a mural in their intersection in order to slow traffic and create a local identity. They didn't ask permission from local government, because they knew they wouldn't get it. The project was so successful, however, that Portland is now one of many cities around the world that permits such murals.

Activists in San Francisco started feeding the parking meters so that they could create gathering places in parking spaces for a day. Now, International PARKing Day is observed in cities everywhere. And, many of those temporary parklets are now permanent. Palmerston North, New Zealand is one city that has many parklets. The local government gives community activists a Placemaking Toolkit which includes a Get Out of Jail Free card "if you unwittingly contravene a regulation in your effort to make your city a better place."

Culture of Sharing

There's a lot of talk about the sharing economy these days with the popularity of businesses like Airbnb, Uber and Zipcar. Less heralded but a much greater force in community building is the growing culture of sharing. Unlike the sharing economy, it is tied to relationships rather than money.

One of the simplest expressions of the culture of sharing is the little free library. The first one was built in a small town in Wisconsin in 2009 when Todd Bol wanted to memorialize his mother who had been a schoolteacher and book lover. He built a library shelf designed to look like a schoolhouse, filled it with paperbacks, erected it in his front yard, and invited his neighbors to take and leave books. It proved to be an effective way not only to share reading materials but to help neighbors engage with one another. There are now tens of thousands of such libraries in at least 70 countries and the concept continues to evolve. Red Deer, Alberta even has little free libraries in its public buses.

Although the concept of formal time exchanges is nearly 200 years old, the modern version has really taken off in recent decades. The name and the process differ somewhat from place to place, but they generally operate as time banks. A time bank is a network of neighbors who share their skills to meet one another's needs. Everyone's time is valued the same. So, for every hour of service that someone provides, they are entitled to an hour of service that they need from someone else in the network. Not only is it a great way for people get their needs met outside of the monetary system, but it is an effective tool for connecting neighbors who might otherwise be isolated. Time banks are the most prevalent in the United States and United Kingdom, but variations can be found in at least three dozen countries.

The recent proliferation of co-working spaces has also been a major contributor to community building, especially among young people. While most such spaces do require a fee to join, members typically share their expertise freely with one another. I visited such a space in Sioux Falls, South Dakota that was located in a former bakery. The Bakery has plenty of formal and informal working spaces, but it also hosts food trucks, yoga classes, and free workshops offered by the members. The more than 500 young people who belong have formed such a tight community that housing is now being designed for vacant lots around The Bakery so that members can live, learn, work, play and eat all in the same neighborhood.

Similarly, in Columbus, Ohio's old industrial neighborhood of Frankenton, young people have renovated a former factory as the Idea Foundry. A membership fee gives them access to shared space and equipment such as pottery kilns, welding supplies, and a 3D printer. A nearby warehouse has been turned into 200 artist studios accompanied by a pub, restaurant and performance spaces. Other former industrial buildings now house a glass studio and a brewery. This young entrepreneurial community comes together each year to host Independents' Days - three days of independent film, music and art.

Social Media

An argument can be made that electronic screens contribute to the breakdown of social capital as face-to-face relationships give way to virtual friends, but social media can also play a role in building community. I've done some work in Wyndham, a quickly growing suburb far outside of Melbourne where the community infrastructure hasn't kept pace with the housing development. Lacking physical bumping places, neighbors turned to Facebook as a way of connecting. A high percentage of the population now belongs to the various neighborhood pages. I heard several powerful stories of neighbors helping one another in times of need even though they had not previously met one another physically.

A key requirement in my community organizing class at the University of Washington is that the students organize around something they are passionate about. One of my students, Megan, said that she had two passions – eating cookies and losing weight. She proceeded to use the Nextdoor social media platform to offer free cookies to residents in her Leschi neighborhood. Megan walked six miles each Sunday delivering the cookies and meeting her neighbors. It turned out that most of them were more interested in the company than in the cookies, and several offered to help with her project. They quickly outgrew Megan's tiny kitchen, so she put out another message on Nextdoor seeking commercial kitchens. Three churches offered theirs.

Participatory Democracy

The decline in voter participation that Putnam noted has continued, but government officials are starting to wake up and realize that they share much of the blame. A focus on good business practices and customer service over the years has left many people feeling like taxpayers rather than citizens. Tokenistic citizen engagement techniques such as public hearings and task forces have only appealed to the "usual suspects." Even voting is viewed by many as an exercise in abdicating power. A true democracy requires much more robust and inclusive engagement. Especially at the local level, public officials are realizing the importance of building community and empowering people to make their own decisions and to initiate their own projects.

One of the first cities that devolved power to the people was Porto Alegre, Brazil which initiated an ambitious process of participatory budgeting in 1989. The process starts at the neighborhood level, involves about 50,000 citizens, and determines which projects and services will be supported with the City's $200 million budget. Cities throughout Brazil replicated this process and now participatory budgeting has taken hold on every continent. In most cities, however, citizens are given a relatively small portion of the budget within which they can propose and prioritize projects.

Many other local governments are empowering citizens to develop their own neighborhood plans. The City of Seattle even made money available so that neighborhoods could hire a planner accountable to them. Rather than start with the City's budget, this process starts with diverse interests coming together to develop a shared vision for the future of their neighborhood and developing recommendations for actions that will move in that direction. Unlike traditional planning, these bottom-up plans tend to be more holistic, get many more people involved (30,000 in Seattle) and leverage the community's resources as well as local government's.

Another tool for leveraging community participation and other resources is the Neighborhood Matching Fund which was developed by the City of Seattle's Department of Neighborhoods in 1989. The program supports informal groups of neighbors to undertake one-time projects by providing a cash match in exchange for the community's match of volunteer labor. Through this program, more than 5000 community self-help projects have resulted – new parks, playgrounds, community gardens, public art, cultural centers, renovated facilities, oral histories, etc. The City's $70 million investment over the years has leveraged $100 million in community contributions that otherwise never would have been tapped. But, the best benefit is that it has involved tens of thousands of citizens with one another and with their government, often for the first time. Now, there are hundreds of such programs around the world but none on the scale of Seattle's.

Participatory democracy is catching on in many parts of the world. In the Netherlands, where there are numerous examples of community-driven planning and participatory budgeting, the movement is called Burgerkracht (Citizen Power). Machizukuri is the term for community building in Japan; first codified by Kobe City and utilized in recovering from the 1995 earthquake, a similar approach to citizen engagement in the development process has been adopted in other east Asian countries. In New Zealand, the movement is called Community-Led Development and builds on Maori concepts. Australia's Municipal Association of Victoria sponsors an annual Power to the People conference; there are now many examples of community-led plans and matching fund projects throughout the State of Victoria. In Iceland, Better Reykjavik involved 40% of the population in submitting and voting on ideas via the internet; that success led to an effort to crowdsource a new constitution for the country.

In Canada, there is a focus on building community at the neighborhood level. The Ontario Cities of Burlington, Hamilton, Kitchener, London and Toronto have engaged in widespread consultation to develop comprehensive Neighborhood Strengthening Strategies. The City of Edmonton and smaller jurisdictions throughout Alberta are training block connectors to bring neighbors together around shared interests and for mutual support. In British Columbia, the Vancouver Foundation is working with local governments to make small matching grants available in 17 communities.

Other

Although I have tried to categorize the new forms of community building, I should note that community ways defy categorization. It's in community that everything comes together, so the approach is typically holistic. For example, Veg Out community garden could be categorized as a local food, environmental or placemaking project or as an example of community-created art or the culture of sharing. Every case cited above could also be described as a public safety or health promotion project because both benefit from stronger social capital. At the same time, there are many new forms of community building that don't fit in any of the categories I have listed. Here are a few examples.

The increasing frequency and ferocity of floods, droughts, fires, tornados, hurricanes, earthquakes and other disasters throughout the world is prompting communities to take the initiative in preparing for disaster. Neighbors are meeting one another, sharing their contact information, and making plans to combine their skills, equipment and other resources so that they can be as resilient as possible. Vashon Island, Washington, where I live, has 200 Neighborhood Emergency Response Organizations. Volunteers also created and operate a network of ham radios, a Facebook page, and radio and television stations for emergency communication; in the meantime, these media play a significant role in further building the community connections that are key to resiliency.

Neighbors are finding new ways to support their elders so that they can age in place. In a small village outside of Hoogeveen in the Netherlands, neighbors renovated a former restaurant to serve as an assisted-living facility staffed largely by volunteers. The other elders are supported to stay in their homes by neighbors who serve as "Buddies" - making regular visits, providing rides, and helping to maintain the house and yard. Neighbors are playing a similar role in cities throughout the United States where Virtual Villages have been organized. Started in Boston, this model also helps isolated seniors to connect with community and offers concierge-like referrals for those services that can't be provided by volunteers.

Collective knitting may seem like a frivolous activity by comparison, but it is also playing a role in rebuilding community. Knitting groups are popping up everywhere whether their purpose is to knit apparel for newborns, pussy hats for the Women's March, blankets for homeless encampments or to create street art through yarn bombing. In the Voorstad neighborhood of Deventer in the Netherlands, eight women came together to socialize while they knitted scarves in the yellow and red of their beloved football team, the Go Ahead Eagles. The movement grew and soon there were knitting groups everywhere, even in the football stadium. Several months ago, they sewed the scarves together and completely covered a house to show the warmth they have for the Syrian refugees who live inside. Their current goal is to make a scarf so long that it can surround the entire neighborhood; the 185 men and women participating in this project are three kilometers of the way towards knitting their community together.

I hope that you are as heartened by all of this as I am. Community isn't an old-fashioned concept. We need it now more than ever. But, if we are going to build stronger communities, we can't hark back to the old ways. We're living in a different world, and we need to adapt our approaches accordingly. Fortunately, people are stepping up everywhere and continually finding new ways to connect with others. I can't imagine a more exciting time than this for building community.